When Abundace is Worth Dying For

Two Contrasting Songs of the Shirt

I. The Handloom Weavers

“We held on for six weeks, thought each day were the last;

We’ve tarried and shifted till now we’re quite fast.

We lived upon nettles while nettles were good

And Waterloo porridge was the best of our food.

I’m a four-loom weaver as many a one knows;

I’ve nowt to eat and I’ve worn out my clothes.

My clogs are both broken, no looms to weave on,

And I’ve woven myself to far end.”

—Ballad of the Four Loom Weaver

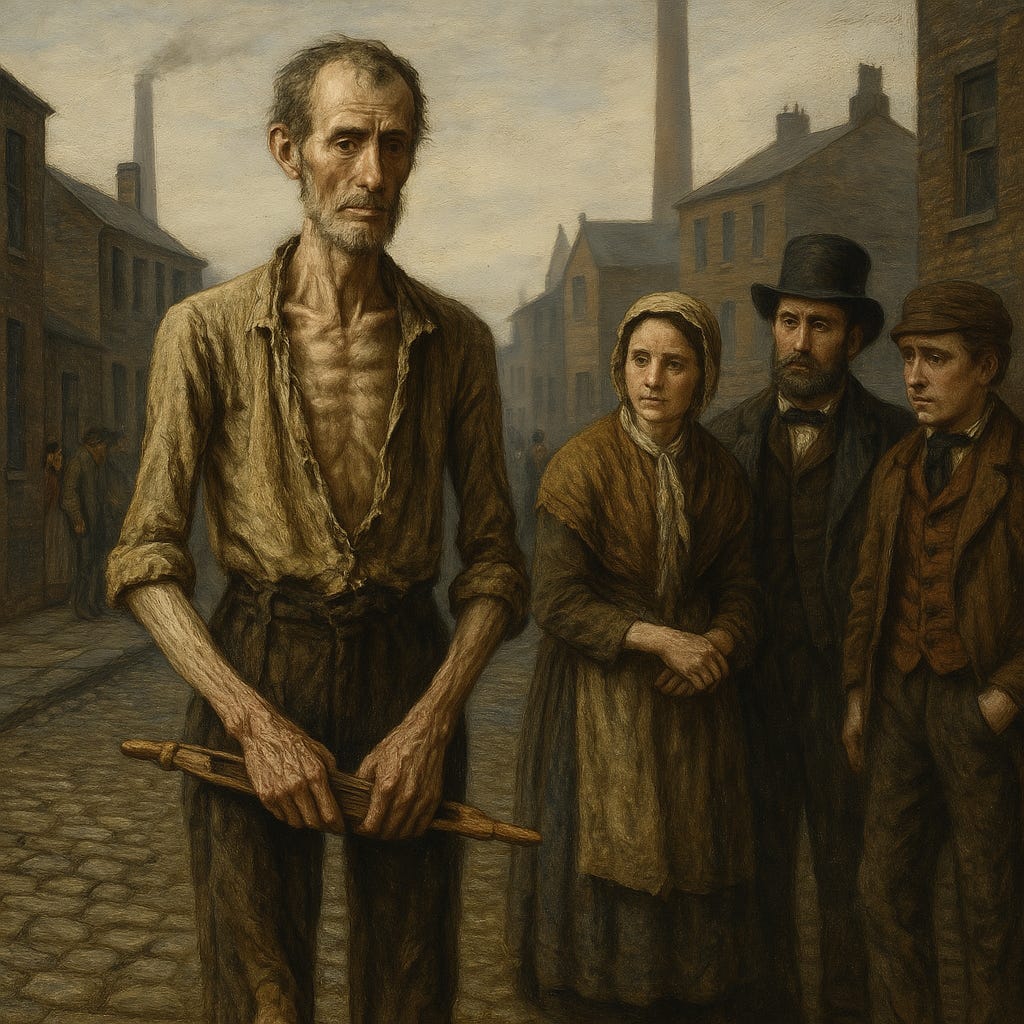

English handloom weavers were on the wrong side of industrial history. For centuries, they were skilled artisans, weaving yarn into cloth and earning two to three times as much as agricultural laborers. They gained modestly from the early Industrial Revolution as innovations in yarn spinning lowered costs and broadened their market. Yet when weaving itself became efficiently mechanized, their world collapsed.

The economics of their trade were simple: income depended on the difference between fabric and yarn prices multiplied by the number of articles produced. Because hand weaving was a mature, static technology and working hours already taxed human endurance, weavers were vulnerable to falling fabric prices. Between 1810 and 1850, the relentless efficiency of power looms caused cloth prices to plummet by 50 to 75%. Yarn prices fell similarly, so a weaver’s profit per article decreased by between half and three-quarters. A dynamic company can withstand such shocks through streamlining and increasing production. It was physically impossible for handloom weavers to increase production enough to maintain revenues. Their incomes fell by between 50 and 75%, leaving them worse off than agricultural laborers and placing many on the ragged edge of starvation.

To understand how devastating this was, imagine a handloom-weaver household of six in 1810, earning a typical wage of 21 shillings per week and spending two-thirds (14 shillings) on food. With bread priced at about 2 pence per pound, 14 shillings (168 pence) bought over 80 pounds of bread weekly, leaving just enough for modest amounts of cheese, bacon, or potatoes. Divided among six people over seven days, this provided roughly 90,000 calories per week—about 2,200 calories per person per day—along with adequate protein from wheat and occasional meat. Typically, calories would be concentrated in the adult male, whose nutritional needs and economic value were greatest.

A 67% reduction in income would be devastating. Skimping on clothes and fuel could not evade a catastrophic reduction in nutrition. A family reduced to 7 shillings a week, spending 75% of it on bread, could scarcely afford even 1,500 calories per person per day. Handloom weavers who could not find a different trade slowly starved.

It’s impossible to precisely measure excess mortality among handloom weavers because parish records and early census data often omitted occupation. However, laborious inferential work suggests England’s roughly 300,000 handloom weavers suffered excess mortality of between 5,000 and 20,000 lives between 1810 and 1850.

II Everyone Else

"What were luxuries to the few are becoming necessaries to the many. What the nobility wore yesterday, the middle classes wear to-day, and the working man will wear to-morrow. Cheaper cloth and garments have clothed the masses warmly, protecting them from the bitterness of winter as never before."

—Samuel Smiles, 1859

In early Victorian times, food consumed 60–75% of a working-class family’s budget, and clothing an additional 10–15%. The meager remainder would go toward damp, unsanitary housing and a few sticks of firewood or lumps of coal. Even skilled workers like clerks would often freeze. As Dickens wrote in A Christmas Carol:

"Scrooge had a very small fire, but the clerk's fire was so very much smaller that it looked like one coal. But he couldn't replenish it, for Scrooge kept the coal-box in his own room; and so surely as the clerk came in with the shovel, the master predicted that it would be necessary for them to part. Wherefore the clerk put on his white comforter, and tried to warm himself at the candle."

Common laborers shivered through winter, and the weaker ones often died. In a world where buying warm clothes meant sacrificing food, abundant textiles saved lives.

This is reflected in mortality statistics. Around 1810, rural working-class life expectancy at birth averaged 38–41 years. By 1850, it had risen to 41–45 years. Urban life expectancies did not immediately increase because urban slums were unsanitary and rife with disease. Yet, by the 1870s, even urban workers were living longer lives than their rural grandfathers.

These numbers come from demographic historians such as E. A. Wrigley and Roger Schofield, who analyzed parish records, census data, and vital registration reports. Only toward the end of the Malthusian era did society begin carefully recording births and deaths.

The aggregate benefits of cheaper clothing were likely an order of magnitude greater than the privations suffered by handloom weavers. The 1841 census tallied the population of England and Wales at 15.9 million. This dwarfs the total number of handloom weavers, which peaked below 300,000, counting women and children working alongside husbands and fathers. Each year roughly 300,000 people died, with respiratory infections accounting for 60,000 to 90,000 deaths. That’s 2.4 to 3.6 million deaths from respiratory infections between 1810 and 1850. Even a modest 1% decrease would save roughly 30,000 lives—far exceeding the highest estimates of handloom-weaver mortality. A 25% reduction—entirely plausible when many working-class families lived in unheated homes and struggled to afford blankets—would mean 750,000 lives saved.

Even the crude statistics we have clearly demonstrate that, in utilitarian terms, the suffering of the handloom weavers was worth it.

The 300,000 to 350,000 Britons who died in the Napoleonic wars are venerated as heroes. Yet it’s not entirely clear what their sacrifices achieved. Most Englishmen were fated to live short and threadbare lives whether George III or Napoleon’s viceroy reigned in Buckingham Palace. A pregnant seamstress could not feed herself on the European balance of power or ancient English freedoms that scarcely touched her life. Cheaper clothing achieved more than Trafalgar, Waterloo, and Salamanca combined.

Indeed, the old thirst for military glory owes much to the drabness and poverty of civilian life. The characters in Jane Austen novels were rarely eager to go off to war if they had a decent income, but would fight eagerly if their subsistence depended upon a military commission or their prosperity hinged upon prize money and promotion.

The real tragedy of the handloom weavers is not that they died but that their deaths were unnecessary. Napoleon could only be checked by military force. The handloom weavers who starved might have survived if the gentry and middle classes had sacrificed a few carriages and expensive garments and paid their poor rates more willingly.

Fortunately, our era can achieve progress without privation. U.S. per capita income is 30 to 40 times higher than British incomes in 1810. Basic solidarity can ensure that no one displaced by new technology ever shivers—let alone starves.

ReplyForward

Add reaction

Excellent analysis. Especially like the contrast with the Napoleonic wars