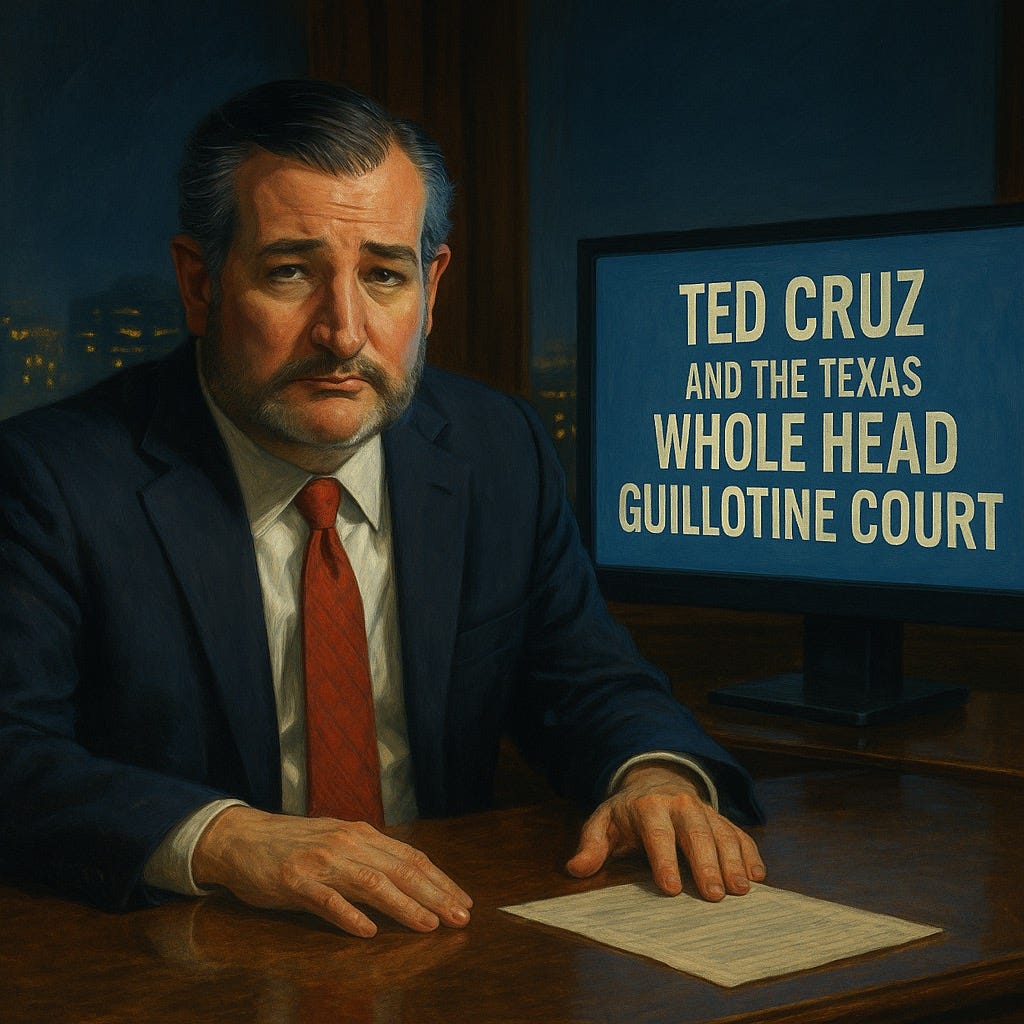

Ted Cruz and the Texas Whole Head Guillotine Court

The senator sat alone in his office as the lights of downtown Washington tinted his saggy red cheeks. He watched cable news the way a gunsmith watches an adolescent with a loaded pistol. The television was unmuted.

The anchor announced gravely that “viewer discretion was advised,” her over-emphasis on disturbing was the only crack in her decorum.

Megan Smelly: “He searched ‘firm C-cups and striped stockings’ three or four minutes before the murder.”

Blitz Wolfer: “Why is this kind of shocking detail important?”

Pierce Bronzeman: “The prosecution wants it to come in to show Orozco was sex-crazed. The defense might spin it as an alibi.”

Wolfer: “One hand was on the phone, the other was busy elsewhere. How could he strangle her?”

Smelly: “But her blood and his fingerprints were all over the knife. He could have acted quickly.”

Wolfer: “But these sorts of things are just unimaginable. How could a person think that firm C-cups and tight stockings could go with murder? It’s unspeakable. I try, but I can’t even think about it.”

Bronzeman: “Firm C-cups can definitely go with striped stockings. The prosecution will have the jury’s attention.”

Wolfer (after a pause): “But that’s what’s so chilling, isn’t it? The ordinariness. These aren’t monsters in a cave somewhere; they’re people who could be your neighbor, your coworker, your accountant.”

Smelly: “Or your husband,” she added brightly, then blinked and sputtered, “I mean, statistically speaking.”

Bronzeman: “Any time your best defense is, ‘I’m a pervert and I can prove it,’ your odds are bad—or your lawyer is crap.”

Wolfer: “But these are the kinds of crimes that force us to ask who we are. About the kind of country we’ve become. About the ways we use social media.”

Bronzeman: “This case says that we, the people of Texas, are going to kill the bad guys—unless the federal courts stop us.”

Wolfer: “Will the Supreme Court ever allow this? They wouldn’t even kill the Federal Reserve.”

Cruz muted the show. These fools had never read the Constitution. They were arguing over the fattest leviathan ever to swim and hadn’t even read its six-thousand-word user manual.

Without brute-forcing a stepwise integration, some of the founders dimly perceived the power of two bodies to expel the third. When two bodies travel through space, gravity rarely produces a collision unless one is vastly heavier than the other. Usually, they carve elegant circles around one another, their speed rising as they approach, their paths bending in kinetic submission, then gravity pulling them back ever more tentatively as they part.

When three bodies are perfectly balanced around an imaginary fulcrum, their paths briefly trace the petals of a heavenly flower before small perturbations bring chaos. Most of the time, two bodies rush toward each other, then attract the third. Predicting which object gets expelled and where it goes is messy. Calculus cannot describe the vulgar movements of three bodies, but enough computing power can approximate them.

The British constitution had two bodies—king and Parliament—in stately orbit.

The founders, some of them former smugglers, recoiled from such harmony. They conjured a third gravitational mass in space: not a king nor a council but a court.

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court and such inferior courts as Congress may from time to time ordain and establish… The supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

Cruz first read the Constitution in middle school and felt smart. He read it several more times in college and won debate trophies. He read it dozens more times in law school and understood well enough to clerk for the Supreme Court. At that point he could have sold his pedantry to the highest bidder, but he preferred being famously smart to being kind of rich. He became Solicitor General of Texas and filed paeans to the Constitution’s majesty in federal court.

Now he was a senator. Congress’s ancient power to take away the federal courts’ ability to speak the law was a sword that Congress rarely swung, wary of forfeiting federal power to state courts. But Cruz had found his Excalibur and imagined a TV ad with him pulling it from a stone in a Baptist church.

Cruz leaned back in his chair and smiled faintly. He didn’t need ChatGPT to draft the law that would carve his name beside Holmes and Marshall. He wished America had a Pantheon like the one in Paris, but squelched the thought, knowing that open admiration of France, even the good parts, was not career enhancing.

His law was laconic:

No federal court shall exercise original or appellate jurisdiction over any judgment lawfully affirmed by the Texas Whole Head Guillotine Court.

Cruz considered adding “Because we live under laws,” as a preamble, but thought better of quoting King Demaratus. His lecture to Xerxes was epic, but he probably was gay.

Cruz titled his creation the Until Now Courts Usually Couldn’t Kill Act of 2026. Its fans, and even some of its enemies, called it UNCUCK.