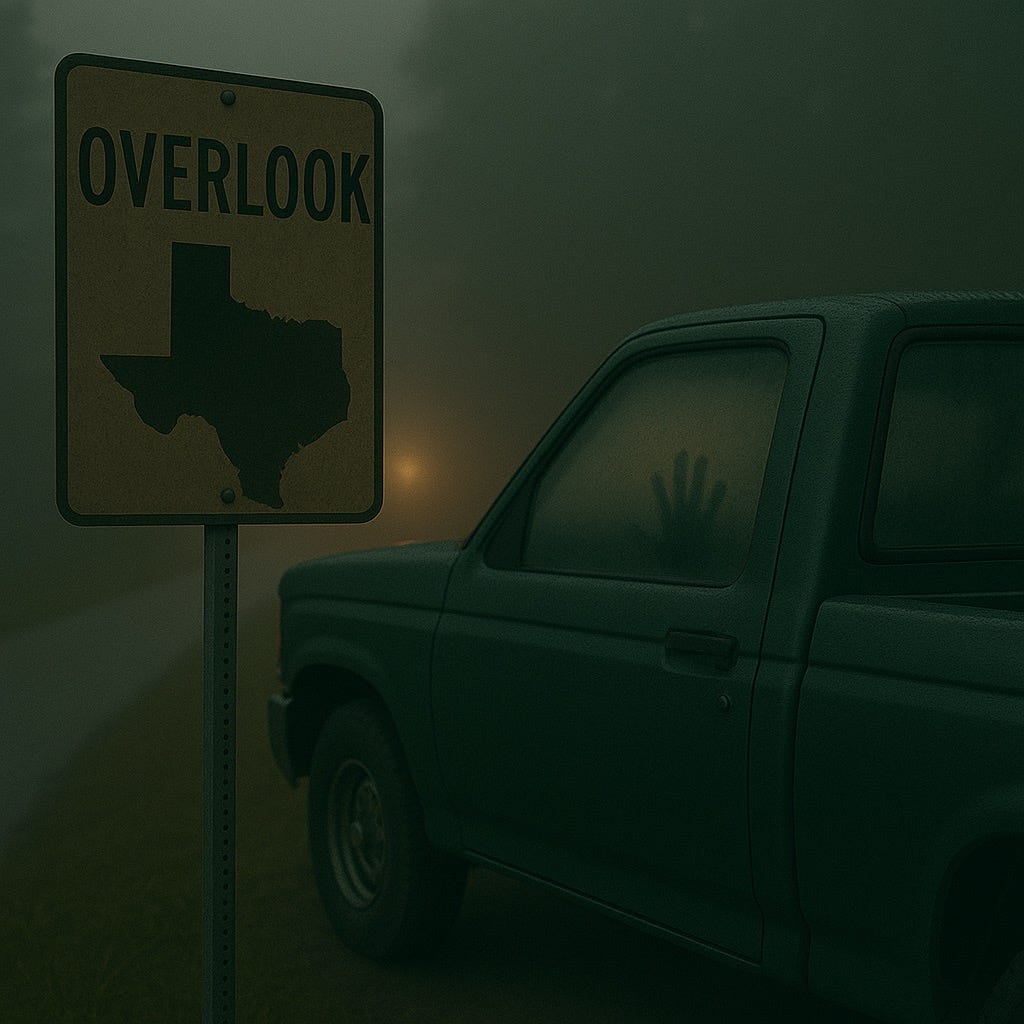

Location is Real

Genesis

In the beginning, there was a lot of gas.

Gravity was the spark that lit the sun,

bound asteroids into planets,

fired their cores,

wrangled airy sheaths from the ancient mist.

The stupid seed of all hope, joy, and fear.

The History of Man

One and a half trillion human eggs have been fertilized. Most never implanted. Of the 117 billion humans born alive, 40 billion died in infancy, a quarter through exposure or outright infanticide. Roughly 28 billion more died in childhood. Ninety-eight percent of those who saw adulthood were peasants, pastoralists, proletarians, or otherwise poor.

Many were slaves. A tiny number became petty officials, small traders, or professionals. Perhaps nine billion learned to read. One billion used the quadratic equation a few times each. Almost none were remembered.

Phil Mason Junior was.

I should have started at the beginning. But time isn’t real, and beginnings don’t hold. You reach back, and vibration is all there is.

I’m okay with verisimilitude; my thoughts are half‑potent, quivering tools. They conquer the surface but never penetrate far. Nothing penetrates the primal buzz. Zoom in far enough and all you have are waves, bent and inscrutable, no loom holding the threads.

The physicists worship their math and say small particles have no real location.

They build a cloud of probabilities using formulas that mostly correct for the vibration of their tools. I’ve learned enough of their math to curse their unsteady tools. Physicists don’t care what one electron does for 1×10⁻²⁵⁰ seconds. You need more than one electron to blow things up, or get tenure.

But if you're stubborn — if you really want to know whether the electron has a fixed location at a single instant — and if you could somehow pursue that question chastely, without tools.

But you can’t. No more than a caveman could have a son without fucking. Tools vibrate. The deepest truths recoil from our tools. Truth will always tantalize.

My virgin muse, I will not forsake you, though your sacred parts hide behind vibration. Trust not the physicists who say you don’t exist when they cannot worship your chastity. Their lonely math is a satyr — priapic, vulgar, and faithless.

Location matters.

On November 7, 2026, in Austin, Texas, Jesus Orozco’s location became his destiny.

Orozco asked for a large dose of benzodiazepines and received it an hour before. He was half asleep. His face lost its power of expression when they strapped him to the steel impression of a 6'1", 220-pound male in the prone position. His face was pressed against a two‑foot‑thick steel mask. Beneath his mouth, there was a one‑inch‑wide cylindrical breath hole connected to a single aperture in the steel block beneath his head. A tablespoon of honey coated the top of the pipe.

A 12‑ton, dentated steel cylinder dangled 16 feet above the aft of Orozco’s cranium. The weight dropped. For 0.97 seconds, quantum uncertainty was Orozco’s only hope. Then, his head exploded between steel. The locations and vectors of the relevant particles were apparent to anyone equipped to measure.

Phil Mason Sr. grew up hard. Not Depression hard. Not even LBJ hard. But hard enough.

When he was twelve, his dad left. By fourteen, he was mowing lawns and washing cars to cover the groceries. At eighteen—the day he graduated high school—he became a roughneck.

Those were good years. Working stiffs could finally afford cars, and they liked them thirsty. Factories from Pittsburgh to Milwaukee were buzzing. Phil worked his tail off. Bought his mom a little saltbox house. Bought himself a big-ass truck.

Then he got appendicitis and couldn’t work. The house was paid off, so he had a place to crash. The truck wasn’t, so the bank took it.

Phil never forgot the humiliation. Walking to his buddy’s apartment before dawn just to bum a ride. Leaving work early—not because he was lazy, but because it didn’t make sense to walk 23 miles home just to get a few extra hours.

After four weeks on his new job, the boss lent him an old truck. Didn’t ask for anything. Just knew Phil was a good man and would make it right. Eight weeks later, Phil was a foreman.

The boss didn’t blink when Phil handed over his first big paycheck and said, “Thanks for the truck.”

Two years later, oil prices slumped. The boss offered Phil equity—if he’d take a 50% pay cut. Phil took the risk. The truck was paid off. So was his mom’s house. He’d heard stories about his grandfather striking it big as a wildcat, then blow it all. Now it was his shot. Three years later, Phil was a millionaire ten times over. Three years after that, Phil Mason, Jr. was born.

Phil Mason, Jr. had the kind of childhood most Texas boys dream about. He wasn’t a great athlete, but he was no slouch. Made the varsity football team sophomore year. Even played some. It didn’t hurt that his father was the most beloved truck dealer in Mid-Texas. Dad struck it rich with oil and ran his dealership with a public spirit. He didn’t give credit easily, but would never repo a good man’s truck.

Phil Jr. didn’t coast, exactly, but the wheels were greased. By junior year, he could have his pick of half the cheerleaders to take out on Friday nights. He knew how to talk to them. Knew when to ask about their fathers, when to compliment their hair. He knew not to push. His hands were more gentle than grasping. That made them trust him — enough to lean in, breasts brushing his flank like it meant nothing. They weren’t trying to cum. Not yet.

Some girls came to him for calm. For shelter from the real jocks they fucked when they were in rut. The defensive tackles with hickeys down their collarbones. The wide receivers who left condoms in the glove box like they were mints.

Phil was different. He’d park in the country and listen to them cry about boys who were meaner, hotter, dumber, better. He’d drive them home and kiss their cheek in fondness and defeat. He was well-liked, but didn’t get laid much.

It wasn’t until freshman year at UT that he met Kara. She had long legs, a half-smile, and a way of talking that made people lean in without realizing it. She wasn’t the hottest girl in the dorm, but she was the one you couldn’t stop watching.