Fighting Hitler Made the Holocaust Worse

Another Reason Yglesias is Wrong and Fighting Unwinnable Wats in Bad

When Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from Munich, his plane flew up the Thames and above London. Looking down, he imagined a German bomber flying the same course. He knew Britain could not protect the thousands of homes stretched out below, and, for this reason, could not countenance fighting an avoidable war. Yet a year later, Britain went to war in a quixotic effort to protect Polish independence.

Few criticize Britain's eventual declaration of war. Chamberlain is more often derided as a coward or naïf for postponing war at Munich. His critics argue that World War Two had moral clarity absent in other conflicts. However, moral clarity demands more than a villain; it requires a clear and effective plan for defeating him. In September 1939, Britain had no viable strategy for defending Poland or projecting power into Eastern Europe. It made no substantial military effort to save Poland; instead, it built its strength while biding its time. Ultimately, the war’s toll was lighter than Britain expected: 451,000 British deaths, barely half as many as World War One. While the Blitz killed around 43,000 civilians, Britain's Committee of Imperial Defense had anticipated 600,000 civilian deaths from air raids in the war's first two months.

Munich occurred before the Kristallnacht in Germany. At the time of Munich, German Jews had suffered less ethnic violence than American blacks under Roosevelt. The Jews killed during Kristallnacht numbered about half the American blacks lynched under Harding. Those seeking moral clarity must look beyond 1939 and even beyond the early stages of the war.

During the war, Germany escalated its atrocities, murdering six million Jews. This fact dominates World War Two historiography and cements the consensus view of Chamberlain as a coward for not confronting Hitler sooner. While hindsight shows Hitler was worse than an antisemitic Napoleon, it offers no practical strategy for resisting him in 1938 or 1939. Britain undoubtedly gains virtue points for opposing Hitler, but awarding genocide prevention or utility points would be dubious.

Britain’s core problem in 1939 was geographic: it could not project military power beyond the Danish Straits into Eastern Europe. Imagine Britain attempting to aid Poland in September 1939. The Royal Navy would need to sail through the three-mile-wide, easily mined Danish Straits under constant German surveillance and within range of German aircraft and artillery. Such a suicidal convoy would likely have been annihilated. Even if British forces miraculously landed, they would face isolation, encirclement, and destruction by German forces. This scenario is beyond implausible—it's outright fantasy. Britain's declaration of war was more an emotional reaction against Hitler’s duplicity than a calculated strategy.

Chamberlain’s Agony

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain loved peace and despaired of achieving much through war. Yet he was pragmatic rather than strictly pacifist. His candor was unusual for a statesman:

“I am myself a man of peace to the depths of my soul. Armed conflict between nations is a nightmare to me; but if convinced any nation aimed to dominate the world by fear of force, I would feel compelled to resist.”

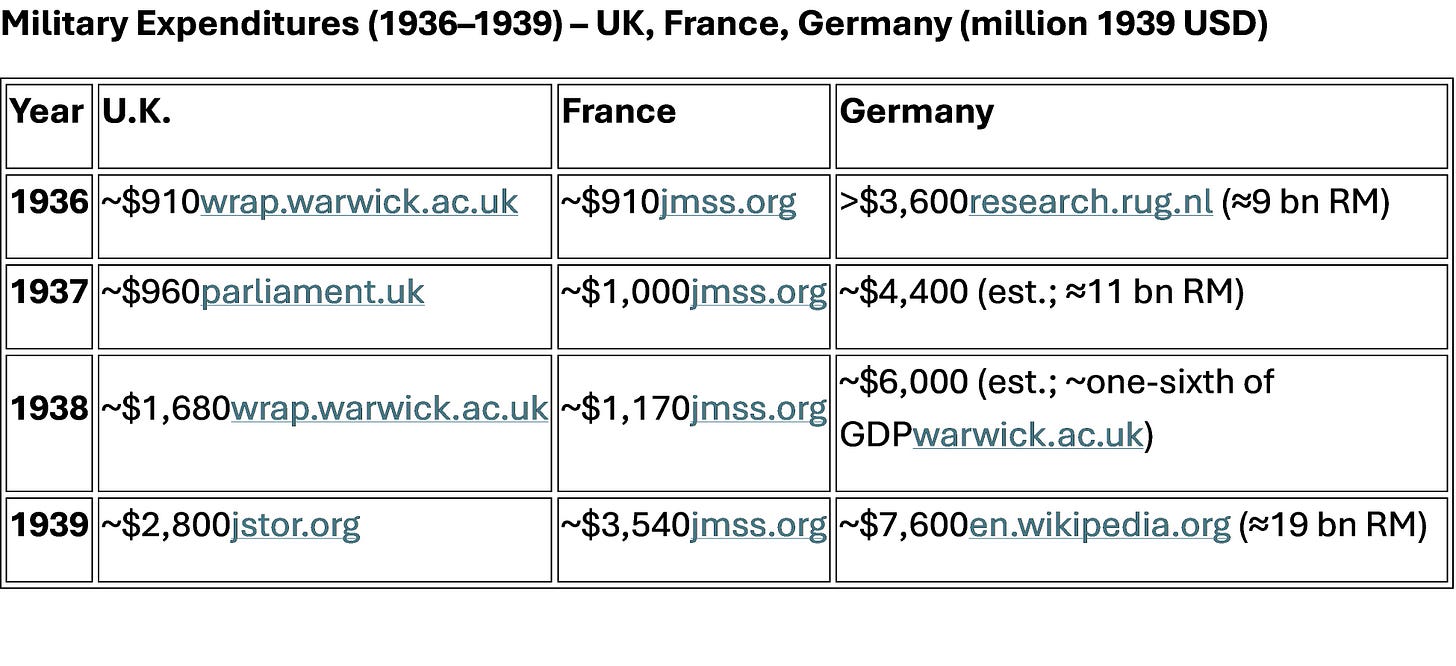

In 1938, Chamberlain sincerely and rationally believed Britain lacked the strength to resist Germany. For three years, German military expenditures had been twice those of Britain and France combined:

Chamberlain understood Britain's military weakness. In January 1938, he wrote privately, “In the absence of any powerful ally, and until our armaments are completed, we must adjust our foreign policy and bear with patience and good humor actions we'd prefer to confront differently.”

In September 1938, when Hitler annexed Czechoslovakia, Chamberlain went to Munich and acquiesced in exchange for Hitler’s promise that he had no further European ambitions. At the height of his popularity, Chamberlain overpromised, reassuring the cabinet, "Herr Hitler has a narrow mind and is violently prejudiced, but…would not deliberately deceive a respected negotiating partner.” Chamberlain thought he had secured “peace in our time" and avoided disaster. After the war began, Chamberlain privately claimed, “Hitler missed his opportunity in September 1938. He could have dealt Britain and France a mortal blow then. That chance won't return.” The above table of pre-war military expenditures supports this view.

At Munich, Chamberlain neither sought nor secured promises from Hitler regarding Germany's treatment of Jews. Two months earlier, at an international conference convened to address the growing number of Jewish refugees fleeing Germany, Britain had refused to admit more Jews into Britain, Palestine, or any other British territory. British elites found Nazi antisemitism distasteful but viewed it as an internal German matter. Chamberlain’s attitude, expressed in a letter to his sister months after Kristallnacht, was probably typical of British elites: “No doubt the Jews aren't a lovable people; I don't care about them myself; but that is not sufficient to explain the Pogrom.”

When Hitler broke his promise of no further annexations and invaded Poland, Chamberlain was shattered. On September 3, 1939, as war began, he expressed profound self-doubt:

"This is a sad day for all of us, and none sadder than me. Everything I've worked for, hoped for, and believed in has collapsed. I can only devote my remaining strength to victory. I hope to live to see Hitlerism destroyed and Europe liberated."

By late 1939, Chamberlain saw Hitler as an antisemitic Napoleon who had to be defeated even at great cost. In response to German peace feelers in late 1939, he said, "We’re frequently urged to negotiate with Hitler. Those suggesting this forget we've already negotiated with him. We know the result. It's impossible to rely on any promises Hitler gives." Chamberlain was angry that Hitler had deceived him and was unwilling to let that happen again. His error was that Hitler’s lies did not conjure extra French or British planes or divisions. They galvanized the British will to resist, but did not supply the means of resistance.

Throughout his premiership, Chamberlain took a sober view of Britain’s military strength. In April 1940, he said:

"The common cry, especially in the U.S., is 'Why are we always too late? Why let Hitler take initiative?' The simple answer—though critics won't accept it—is 'We aren't strong enough yet.' We have manpower, but it's neither trained nor equipped. We're short of weapons, particularly air power. If we survive this year, we might overcome our deficiencies."

Ultimately, Chamberlain believed war was necessary because Europe could not be dominated by a lying, half-mad Napoleon. Chamberlain died before learning the scale of the Holocaust.

Britain didn't have an anti-genocide policy

Nothing in the historical record suggests Chamberlain or his Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, gave significant thought before or during the war to genocide prevention. Their silence on this issue suggests that preventing genocide simply was not on their mind. Had Britain cared deeply about stopping genocide, its leaders might have recalled the major genocide committed by Britain’s enemy during the previous war—the Armenian genocide, during which the Ottoman Empire killed over one million Armenians between 1914 and 1916.

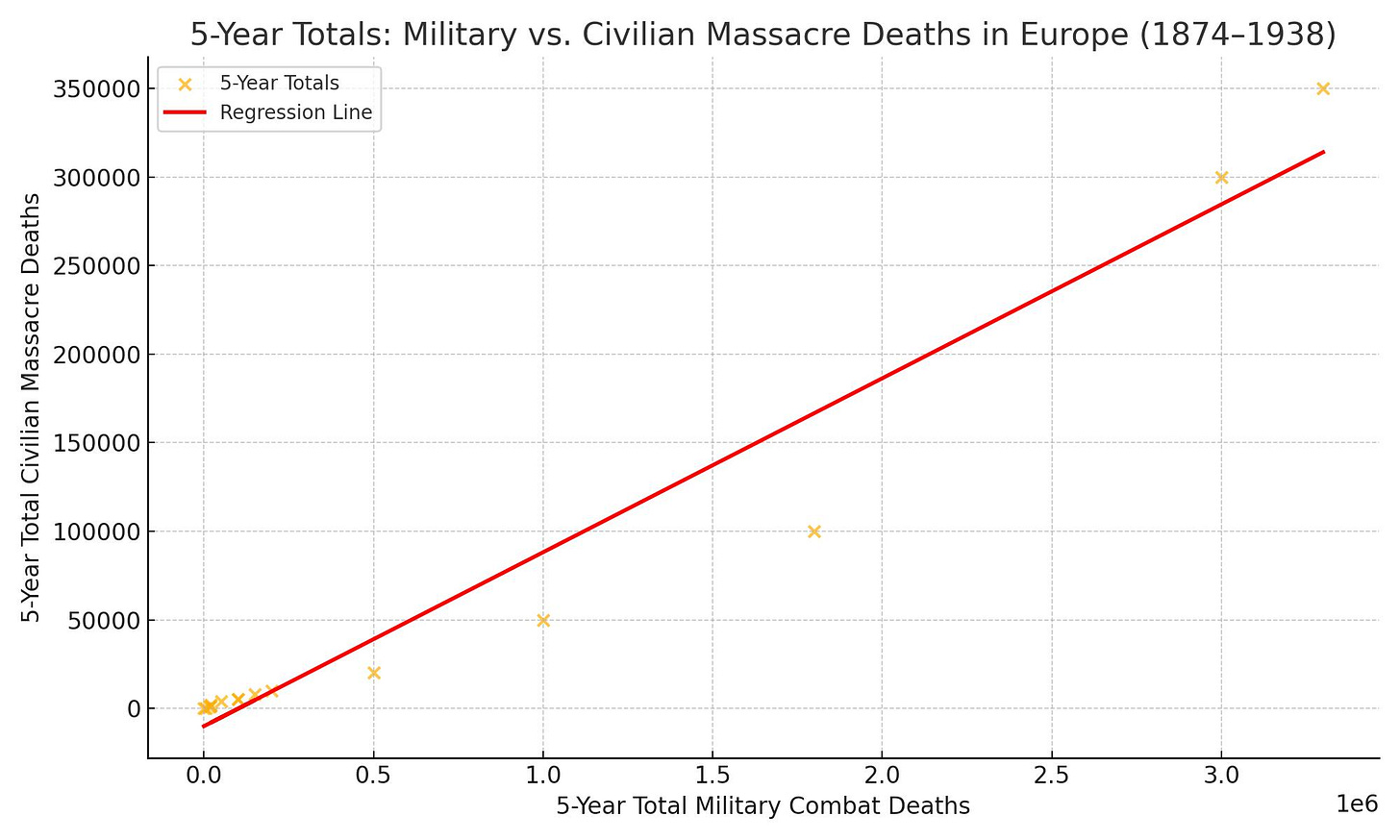

When armies march, civilians die. French revolutionary armies massacred Catholic rebels in the Vendée. Russian forces responding to the 1905 revolution oversaw hundreds of anti-Jewish pogroms. The Ottoman crackdown on the Bulgarian uprising in 1876 killed at least 15,000 civilians. And in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, thousands more died as Christian and Muslim communities embarked on mutual slaughter. Civilian massacre deaths—defined as the sum of civilians killed in pogroms, political and ethnic violence—correlate tightly with military deaths. The following scatter plot uses the number of military deaths in Europe during each trailing five-year period (eg, 1869 through 1873 or 1870 through 1874) to predict the number of civilian massacre deaths in that period. Combat deaths explain 79% of the variance in civilian massacre deaths (this is the R-squared). The odds of this correlation occurring randomly are 1 in 3.25x10^23. The chances of this being statistical noise are lower than the odds of an asteroid causing a mass extinction on any given day.

British officials were aware that the Kristallnacht had occurred in 1938 and knew or should have known antisemitic violence could escalate dramatically during wartime.

Remarkably, Britain entered a war against a more populous, economically stronger enemy without a clear plan for victory. Yet Britain had muddled through before—against Napoleon and the Kaiser—by securing powerful new allies mid-conflict: Russia against Napoleon, and the United States in World War One. A war between Russia and Germany was again plausible, and German atrocities combined with submarine warfare might eventually swing American support toward Britain, first as a source of essential munitions and materials, and perhaps as a military ally.

Britain’s Indian Stepchildren

Claiming Britain was morally obligated to enter World War Two to protect Jewish lives is baldly racist. If Britain's moral concerns went beyond white Anglo-Saxons, it had plenty of half-starving Indian subjects needing food. Helping nonwhite subjects required neither navigating the Øresund under German air assault, storming hostile beaches, nor defeating the Wehrmacht without resupply. Sending cargo ships filled with grain would have been enough.

In 1939, India had a late-Malthusian economy comparable to Ireland a century earlier. British-built railways and modest but genuine famine relief efforts had enabled steady population growth. Bengal's population grew by 43% from 1900 to 1940. Regional famines still occurred, claiming tens of thousands of lives, typically among the elderly and desperately poor. Yet enough laborers and young women had sufficient food to increase the region's population by 79% in the century before World War Two. Growth was gradual rather than explosive, tempered by regular attrition among the weakest and poorest.

However, during World War Two, two to three million Bengalis died in a famine. These deaths resulted not from catastrophic crop failures but from two moderately poor harvests compounded by Britain's unwillingness to spare ships or grain while the homeland was threatened. The logistical network that had enabled sustained population growth failed. These millions of deaths represent part of the immense opportunity cost of the war.

As Matt Yglesias has observed, politics is the slow boring of hard boards. It's easy to fantasize about British policies that could have improved the world, such as allowing Jewish immigration into the British Empire and investing in Indian nutrition assistance rather than warfare. Obviously, this did not occur. The mass migration of Jewish refugees posed the same political problems that admitting large numbers of asylum applicants posed for President Biden. Americans disapproved of Biden's immigration policies 54 to 26, because admitting large numbers of struggling foreigners who don’t speak the dominant language is generally unpopular. War was politically more acceptable to British elites and voters than mass migration. This is best explained by our Malthusian instincts. Humans have a primal fear of others who will compete against them for food or land. By 1938, the British government was concerned enough about wartime food shortages that it began stockpiling non-perishable foods. In such a climate, letting in additional mouths to feed was bound to be unpopular.

Evaluating British policy decisions in 1939 primarily through the lens of Jewish lives is thus peculiar. The strongest defense of Britain's actions—that it sort of kind of foresaw the Holocaust and nobly confronted Hitler—is based on doublethink. If Britain indeed anticipated the Holocaust, then restricting mass Jewish immigration was monstrous. If Britain did not anticipate the Holocaust, the balance of power in Europe was a dubious reason for war on the scale that defeating Hitler would require. Either way, war was best postponed until and if Britain or possibly France were attacked.

In 1939, the Holocaust was a risk, not a certainty. Any competent statesman would have known that military escalation raised the risk of civilian massacres. Valorizing a policy that left Eastern Europe in Soviet hands, reduced Britain to a second-rate power, and saw two-thirds of European Jews exterminated is perverse. Fighting bad guys isn’t enough. You have to kill them before they kill millions of innocents.