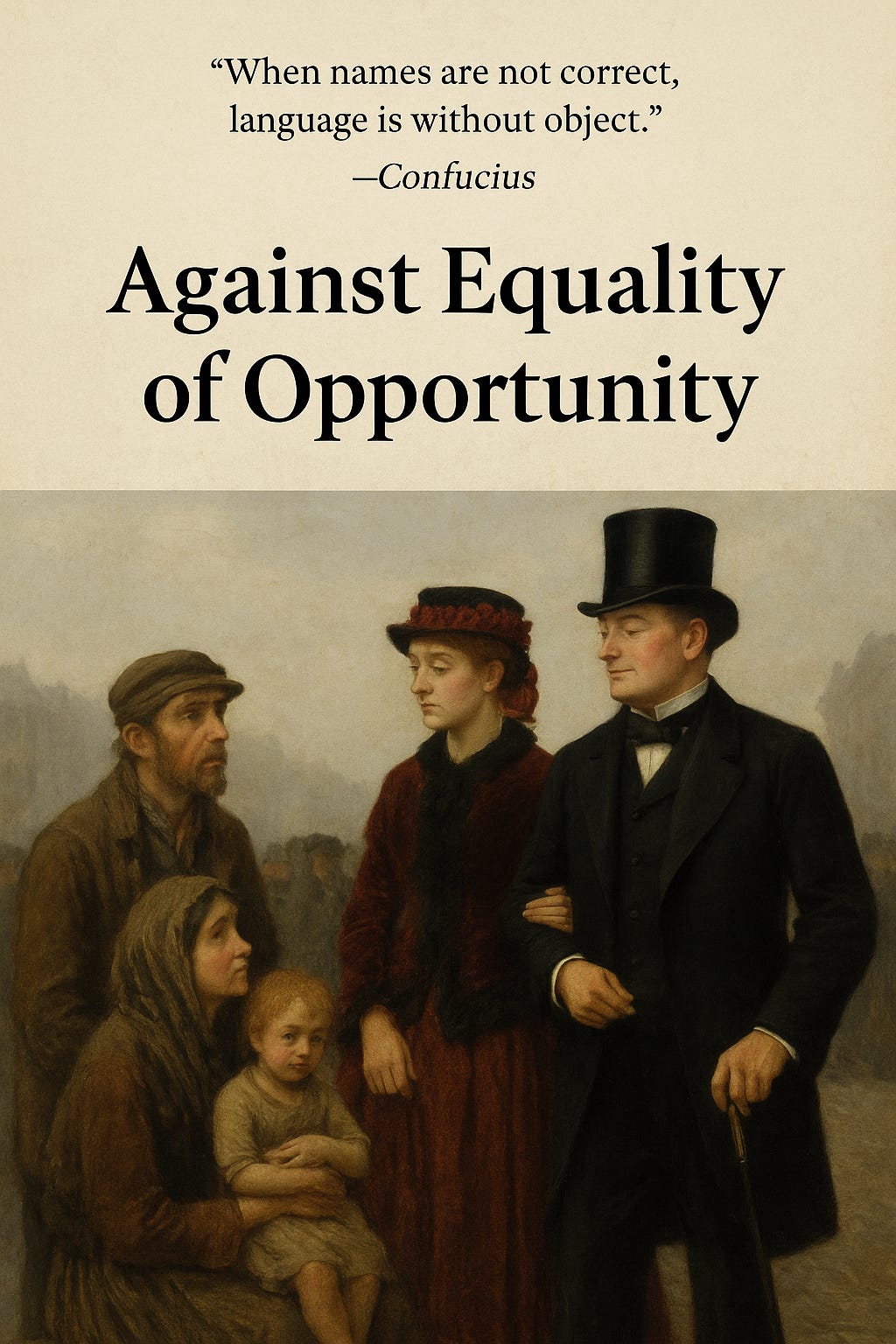

Against Equality of Opportunity

“If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language is not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.”

— Confucius, Analects 13

Equality of opportunity is the laziest lie in American politics. Conservatives wave it like a permission slip for indifference—cover against looking like racists or corporate stooges. Progressives brandish it to signal they’re not wild-eyed communists intent on erasing all distinctions. The slogan thrives because it is comfortably vague and as politically convenient as waving the American flag. Yet it withers upon scrutiny. I will never be a professional athlete, nor a great artist, nor a world-class chess player, because I lack the talent. No amount of schooling, parental investment, or diligent effort would have bridged that gap. The same applies to professions like medicine or engineering: a kid with an IQ of 80 will never have the same opportunity to become a doctor or engineer as one with an IQ of 130.

Proponents of equal opportunity retreat to counterfactuals. They say: yes, Johnny is unlikely to be a doctor because he's not good at tests, but he had a chance of being born smart. If he’d been smarter and there were equality of opportunity, he would have become a doctor. But what does this prove? Was Johnny a homunculus floating in the ether, waiting to be assigned traits at birth? That is not fairness but consolation by fantasy. The hypothetical homunculus lottery isn’t much use to those who play it and lose. A slave could have been born free, a Gazan could have been born a Jew, a paraplegic could have been Usain Bolt. Even if these assertions are true, they make no difference once the dice are thrown and homunculi have actual bodies—and some of them are getting the shaft.

Nor is equality of opportunity a chill, undemanding standard that moderates can embrace while keeping their big ass trucks and international vacations. By definition, equal opportunity means group outcomes converge if the sample is big enough—a direct corollary of the central limit theorem. Flip a coin 10,000 times: 99% of the time, you’ll get between 48.7% and 51.3% heads. In social terms, 10,000 is small—plenty of rare diseases affect more. The number of groups whose outcomes would need to converge for "equal opportunity" to prevail is, conservatively, in the thousands. Even a couple of significant gaps between groups of 10,000 would be inconsistent with the principle of equal opportunity.

Equality of opportunity can be coherent if restricted to particular domains. The idea of equal opportunity to eat nutritious food is perfectly sensible: apart from a handful of people with serious digestive problems, most can partake in this rough equality when food is affordable. When this happens, outcome gaps shrink. In Britain, when working-class nutrition improved between 1880 and 1980, class differences in height largely disappeared: the gap between upper-class and laboring men, which had been nearly 3 inches around 1880, decreased to less than an inch by 1980. This is a case where the phrase “equal opportunity” does have a coherent meaning—restricted to a concrete domain like food—because most bodies digest food in roughly similar ways.

Even here, though, equality is a dubious goal. The increase in working-class heights that occurred as food got cheaper looks like an egalitarian triumph. But the real triumph was in increasing global food production, not in the distribution of culinary opportunity. If society produced only 1,000 calories per person per day, it would be better to feed half the population adequately than to have everyone slowly starve.

There is far more variance between human nervous systems than between digestive systems. When we move from nutrition to education and careers, simple dose–response relationships break down because people differ enormously in their abilities and interests. Since World War II, the Nordic countries have torn down many barriers to women pursuing careers, yet women still cluster in certain fields. In Norway today, over 90% of nurses are female compared to only about 20% of engineers. It is difficult to know what equality of opportunity even means when men and women want such different outcomes.

While equal opportunity is a vain delusion and a chimerical concept, mass education is the fertilizer of progress. In the mid-19th century, basic schooling became broadly available. This did not mean literacy and numeracy between classes converged completely, nor that all classes were equal in ability. But it did mean that bright lower-middle-class kids could finally cultivate their abilities and become inventors and engineers. Even if landlords’ sons had higher average IQs and better educations, the working and lower middle classes were so much larger that they contained most of society’s cognitive potential. As a broad middle class gained access to education, a greater proportion of geniuses got a chance to prove themselves, and technological progress accelerated to an unprecedented degree. Society prospers when it tutors the brilliant peasant rather than promoting the dull heir.

Meritocracy achieves a form of fairness that equality of opportunity never can: it harnesses exceptional talent for the benefit of the ordinary. A truck driver may have relatively low status, but his productivity and wages are massively increased by trucking technology. A world where everyone had an average, or even somewhat above-average IQ would never have produced the internal combustion engine or antibiotics. The gains from cultivating the most capable minds are not confined to those individuals. They spill outward, raising living standards for millions of “normies” who want a steady 9-to-5 and are incapable of brilliant innovation.

In career terms, I am a normie. I make my money as an attorney, not as a brilliant innovator. Yet the purchasing power of my income has grown because of genius-driven innovation. In 1955, a one-way ticket from Atlanta to Paris cost over two weeks of the median attorney’s wages. Today, an average attorney can earn airfare from Atlanta to Paris in 1.2 days of work. Perhaps my work is easy or routine enough that DEI in law school admissions wouldn’t be much of a drag on GDP. But any failure to cultivate the geniuses who will drive the next wave of technical progress would deprive humanity in 2095 of the same kind of advances that made my own life easier than my great-grandfathers’.

Progress comes not from making opportunities equal but by making them broad enough to leverage the cognitive potential that extends across social boundaries. "Equality of opportunity” is a false flag that flatters fantasy. If we care about words matching realities, then we should speak of merit, education, and extending the blessings of abundance as broadly as possible. Only then does the name align with the thing.

I basically agree with you, but I and I feel like most people use “equal opportunity” as a shorthand for “making [opportunities] broad enough to leverage the cognitive potential that extends across social boundaries.”